Market News

Wall Street has a recession obsession. What does the data say? - REUTERS

By Howard Schneider, Dan Burns

(Reuters) - A favorite Wall Street harbinger of business-cycle downturns sent up a warning flare that a recession may be on the horizon on Tuesday, just hours after the latest data on the U.S. economy showed business demand for workers remained strong and consumers were still confident despite some worries about inflation.

It was a disjointed set of events - strong economic fundamentals against signs of anxiety in the bond market - that showed just how tight a path the Federal Reserve will need to walk as it tries to tame inflation with a steady series of interest rate increases.

For traders who briefly pushed rates on the 2-year Treasury note above that of the 10-year Treasury note, the biggest risk to the economy may now be a central bank that finds inflation has slipped its grasp and is forced to act more aggressively than expected, killing the current economic expansion in the process.

Former New York Fed President William Dudley, writing for Bloomberg, even called that outcome “inevitable,” the result of the Fed waiting until this month to raise interest rates even as inflation accelerated last year.

After briefly dipping below zero, the spread between the 10-year and 2-year note yields had widened by mid-afternoon.

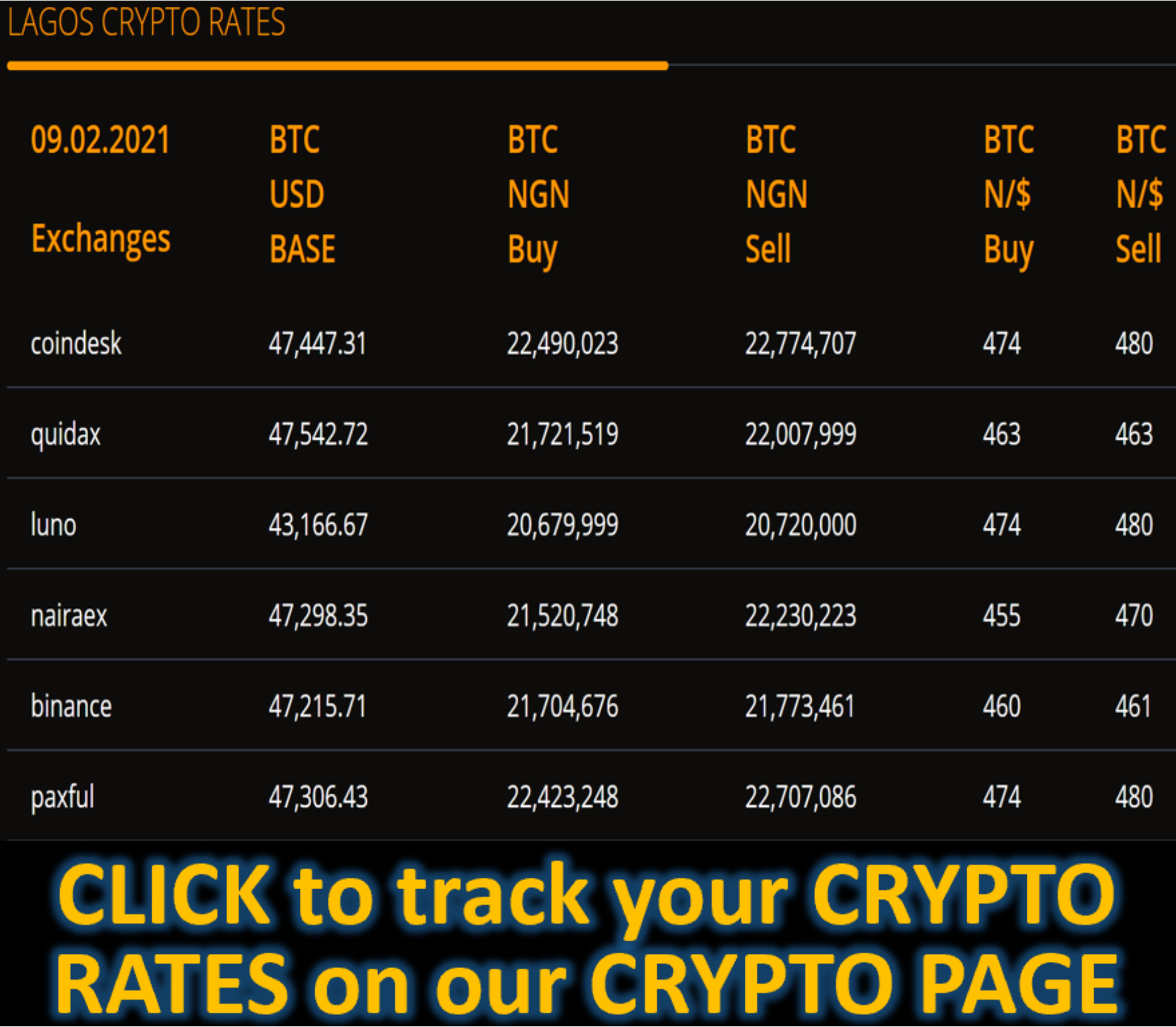

U.S. Treasury yield curve inverts

But the episode still adds a new complication to the debate at the Fed about how far and fast to raise rates, and may even be an indicator in itself of how much the central bank is out of synch with inflation running at triple its 2% target.

Yield curve inversions typically come late in Fed hiking cycles as bond investors sense the central bank may have gone too far in raising borrowing costs and begun to slow the economy.

In the current tightening cycle, the Fed is only getting started. Earlier this month it raised the target federal funds rate by a quarter of a percentage point, the first hike since 2018. The funds rate was cut to the near-zero level to bolster the economy at the outset of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

Fed policymakers expect to raise rates steadily through this year and well into next to bring inflation back to their target - with little scope to worry about what that is doing to the yield curve.

Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker on Tuesday dismissed the flattening yield curve as only one signal that markets were sending in an economy that overall looked healthy and far from recession.

“We are starting in such a strong position going in” to the rate hike cycle, Harker said in an interview with CNBC.

In earlier remarks to the Center for Financial Stability in New York, Harker said: “As a policymaker, I have to look at the combination of all those numbers and come up with a pragmatic path of policy and not base it upon any one.”

For now, the numbers that matter most to the Fed concern inflation, running at a multi-decade high, and a real economy that seems not just strong, but strong enough to weather the higher interest rates the central bank is planning.

Hard to find a job in America? Nope!

American consumer confidence ticked up this month, according to the Conference Board, with a record percentage describing jobs as “plentiful” - data supported by government figures also out on Tuesday showing nearly two job openings for every unemployed worker last month.

The Labor Department is expected to report on Friday that the U.S. economy gained 490,000 jobs in March, according to a Reuters poll of economists, marking an unprecedented 11th straight month of gains above the 400,000 mark. The unemployment rate is forecast to drop to a pandemic-era low of 3.7% - just two-tenths of a point above where it was when COVID-19 struck.

Consumer spending has held up through repeated waves of the coronavirus over the past two years, with goods consumption the strongest in a generation. And, while inflation and rising interest rates may start denting the appeal of big-ticket purchases like cars, signs are emerging that Americans are shifting back toward pre-pandemic spending habits that favor services like travel and dining out.

The risks certainly are real, with the Fed staking its credibility on bringing inflation steadily down. If improvement isn’t seen soon on the inflation front, policymakers have said they would favor hiking rates in larger increments and to higher levels until that happens. That’s the very dynamic that can increase the risk of a recession, and drive short- and long-term bond yields to invert.

What it signals at this stage remains to be seen.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other U.S. central bank officials say they do keep an eye on the yield curve, but won’t necessarily react to it.

“We take it into account, along with many other financial conditions,” Powell said in January when the spread between the 2-year and 10-year Treasury notes was still a healthy 0.75%, but “I don’t think of it as some kind of an iron law.”

Reporting by Dan Burns and Howard Schneider; Editing by Paul Simao