Market News

Financial globalisation and inequality: Capital flows as a two-edged sword - VOX EU

Barry Eichengreen, Balazs Csonto, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Zsoka Koczan 14 January 2021

Global inequality has fallen in recent decades, but within-country inequality has risen in a significant number of national economies during the same period. This column identifies the channels through which financial globalisation accentuates inequality and suggests how these could be mitigated by accompanying policies.

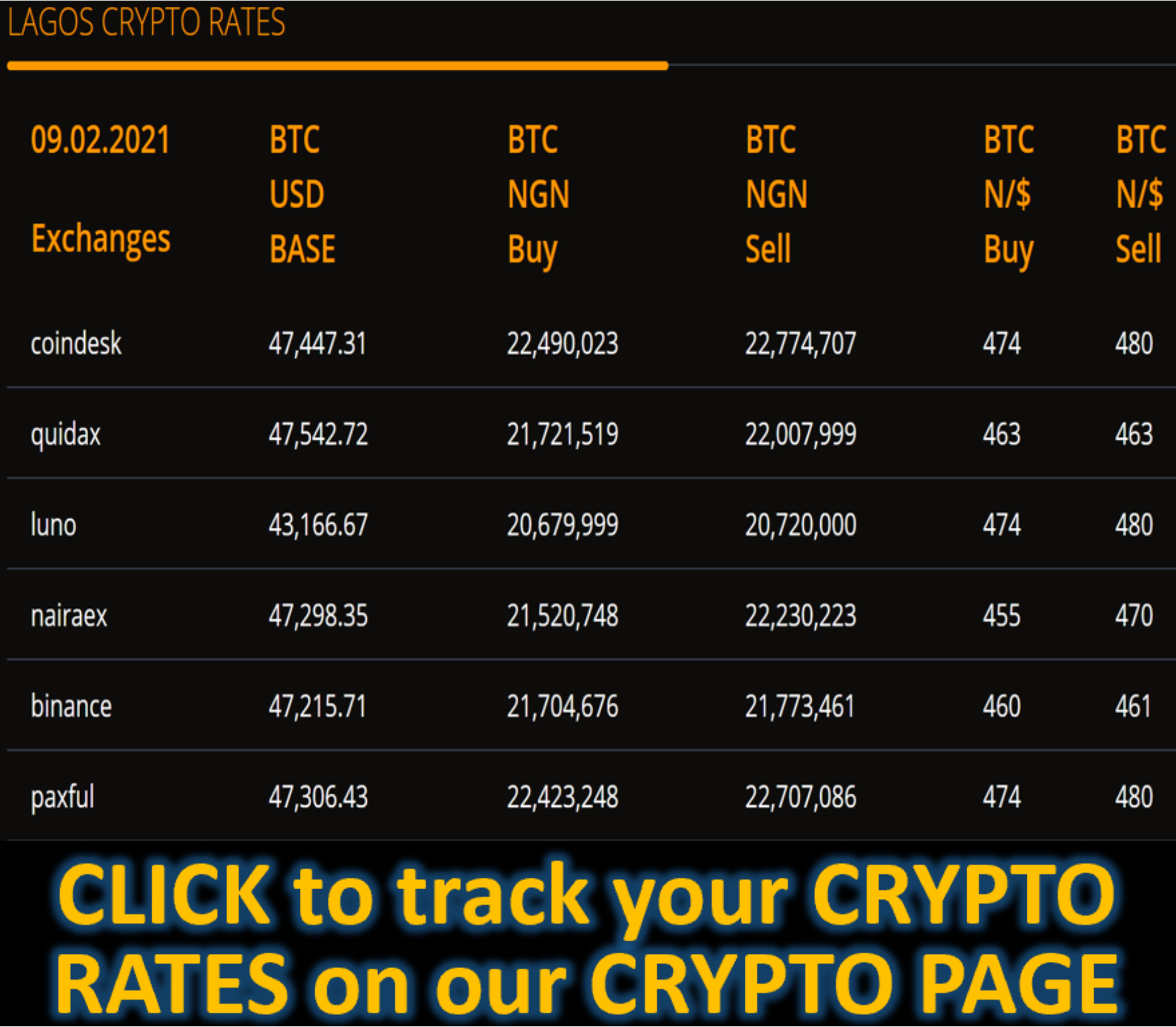

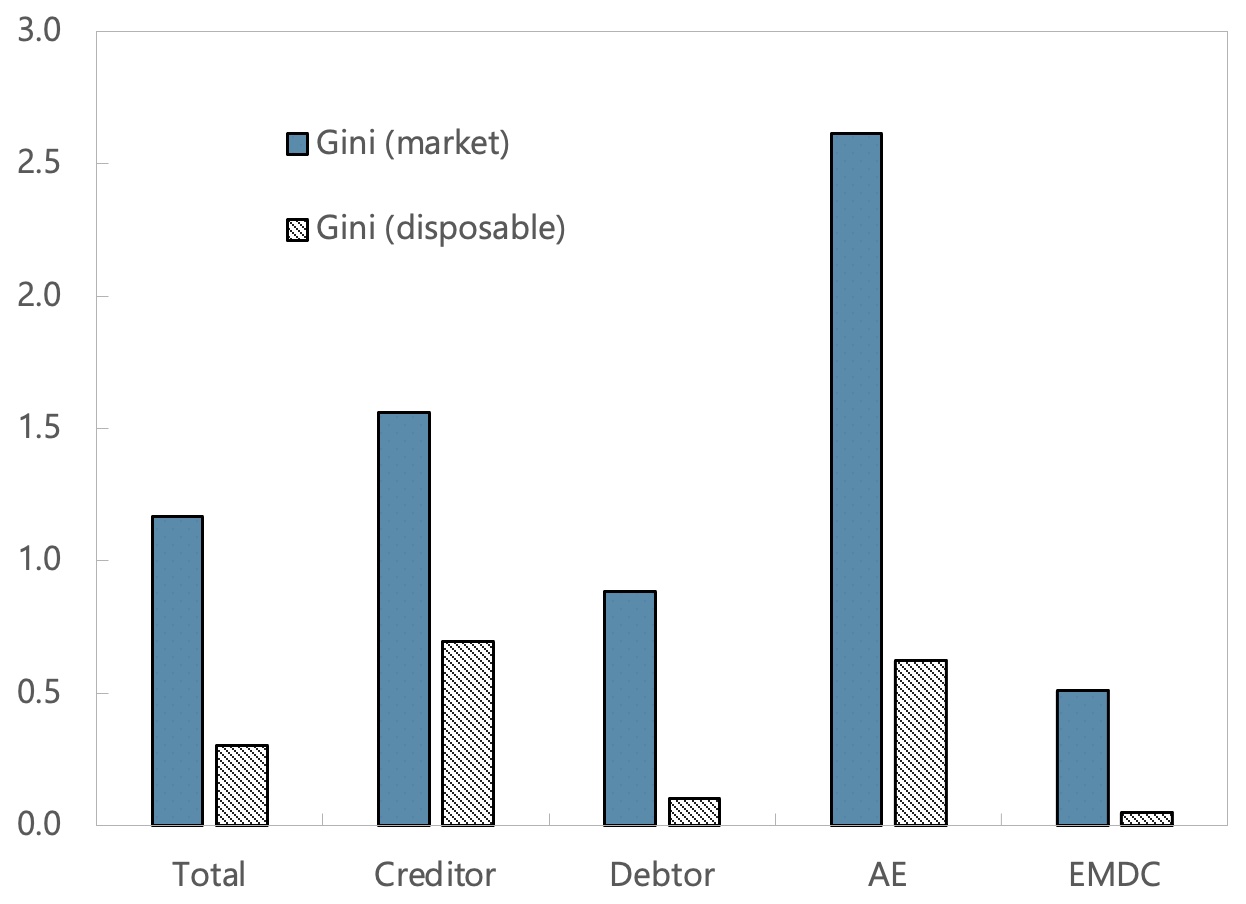

1 shows the change in the Gini coefficient between 1970 and 2015, distinguishing countries with relatively closed capital-account regimes and those that liberalised. The change in inequality was significantly greater in the liberalising countries. The difference was evident for both creditor and debtor countries, and for advanced economies and emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) alike.

Figure 1 Financial globalisation and inequality: Change in the Gini index after capital account liberalisation, 1970-2015 (%)

Source: Chinn-Ito (2006), SWIID 8.1, Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018), and authors’ calculations Notes: The figure shows the median change in the average market Gini index during the 10-year periods before and after capital account liberalisation. Newly liberalised countries are identified on the basis of large changes in the Chinn-Ito index. Specifically, capital account liberalisation occurs when the change in the Chinn-Ito index exceeds its average by at least two standards deviations and there is no reversal of liberalisation over the following 10 years. Closed countries are those with Chinn-Ito Index that is below the lowest value of the index at the time of capital account liberalisation across episodes and those that do not liberalise their capital account over the following 10 years. Creditor (debtor) countries are those with positive (negative) average net foreign assets over the next 10 years. The sample includes 173 countries where a total of 135 episodes were identified (of which data were available for 111 episodes).

Financial globalisation may have other benefits, but to the extent that it accentuates inequality those benefits come with a cost. Even better, the increase in inequality could be mitigated by accompanying policies. Achieving this starts by identifying the channels through which financial globalisation accentuates inequality. In a recent study (Eichengreen et al. 2021), we identify several such channels and recommend mitigating policies for each.

First, financial openness is positively associated with macroeconomic volatility that disproportionately impacts the poor. This volatility can be limited through the application of countercyclical macroeconomic policies. In practice, this mainly means using fiscal policy to lean against the capital-flow-induced wind. The COVID-19 crisis has vividly illustrated the advantages for EMDEs of building fiscal space in advance, in order to stabilise the macroeconomy and support the poor.

Second, financial openness is positively associated with crisis incidence, other things equal, where financial crises also disproportionately hurt the poor. Here capital-flow management (CFM) policies (capital controls for short) can be deployed, as part of a broader policy package, to limit the risk of capital-flow reversals and crises. However, CFM measures should not substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustment. In addition, distributional and social objectives could be considered explicitly in the design of such policies, for example by allowing for housing-related restrictions on non-resident investments where housing affordability is an issue (IMF 2020).

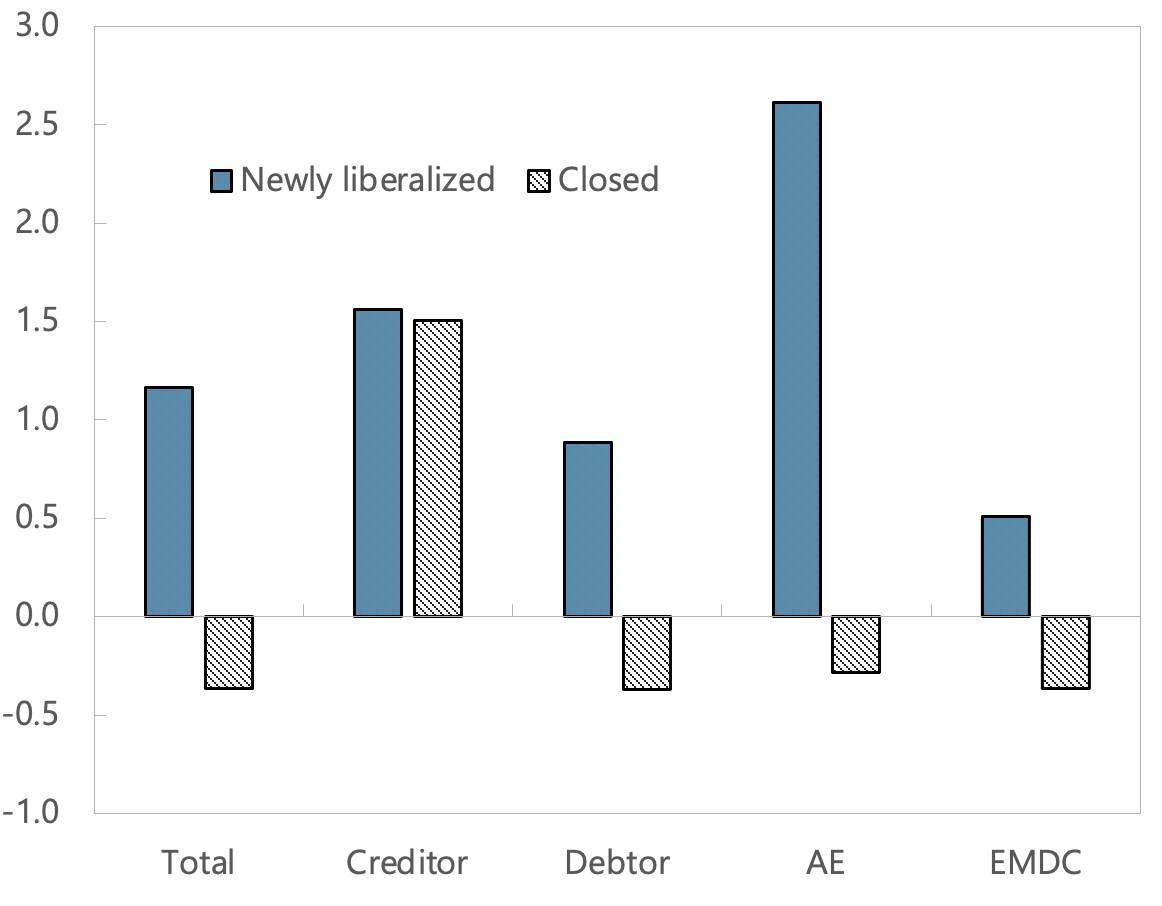

Figure 2 Inward FDI, education, and inequality; emerging and low-income developing countries

Source: Barro and Lee (2013), Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018), SWIID 8.1, and authors’ calculations

Relatedly, ensuring the prudent use of external funds by banks through sound micro- and macro-prudential policies could strengthen the resilience of the banking sector, thereby enhancing financial stability, moderating business cycle fluctuations, and reducing the potential adverse distributional consequences of economic and financial volatility. Similarly, regulatory frameworks that foster competition in banking and finance can facilitate access to credit, and ultimately allow for the benefits of capital inflows, i.e. more abundant credit, to be more widely shared. For example, abolishing credit and interest-rate controls and strengthening banking supervision (e.g. higher powers for the banking supervisory authority, more stringent capital regulation, more monitoring of bank activities) could positively affect financial inclusion and reduce inequality (Delis et al. 2012).

Third, the evidence suggests that the adverse distributional effects of financial liberalisation are larger in EMDEs with relatively low levels of educational attainment. The lower are levels of educational attainment, for example, the fewer workers benefit from the increase in the skill premium associated with inward foreign direct investment. In practice, higher educational attainment is associated with both less inequality and more inward FDI (Figure 2).

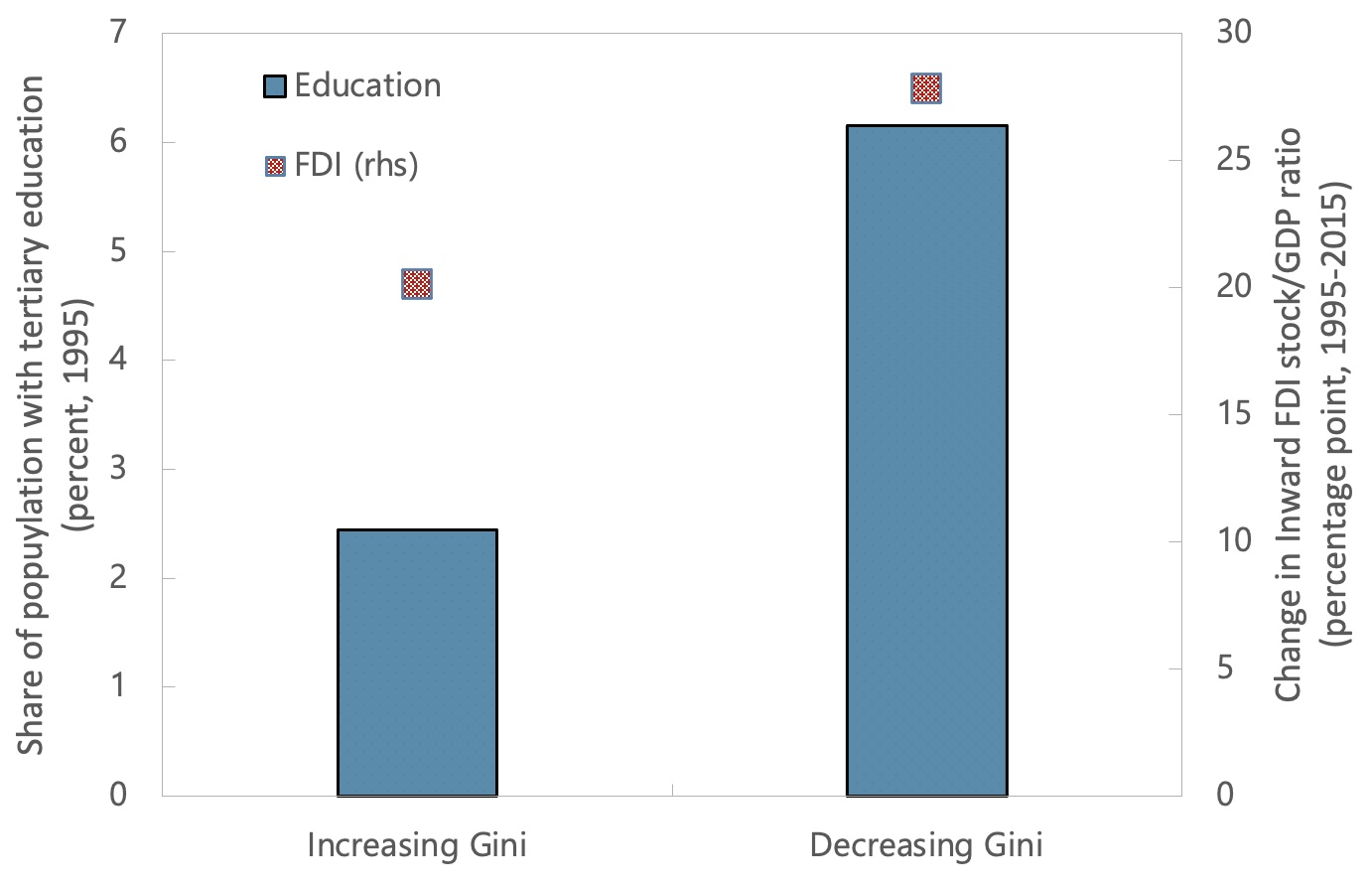

Fourth, there is an obvious role for redistributive policies and social safety nets. Inequality in disposable incomes increases by less than inequality in market incomes following capital account liberalisation episodes, suggesting that redistribution mitigates some of the adverse effects (Figure 3). Because financial globalisation shifts the burden of taxation from more mobile factors (capital and highly skilled labour) to less mobile factors (low-skilled labour), proactive changes in tax and transfer policies are needed to achieve the desired effect (Razin and Sadka 2019).

Figure 3 Capital account liberalisation and gross and net income inequality: Change in the Gini index after capital account liberalisation, 1970-2015 (%)

Source: SWIID 8.1, Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018), and authors’ calculations.

Fifth, financial flows, such as remittances, that disproportionately benefit the disadvantaged should be encouraged. Remittance costs tend to be highest in small markets with little competition, and when remittances are intermediated by commercial banks. Reducing transaction costs, increasing competition, and helping migrants compare costs across providers can increase the net amounts ultimately received by migrants’ families. Mobile technology can also help bring down remittance costs (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2018, Schmitz and Endo 2011).

To conclude, financial globalisation has benefits but also a tendency to accentuate inequality. Its tendency to raise inequality can be limited by policies that shape their composition and timing, and prevent any associated rise in aggregate volatility and increased incidence of crises. That tendency can be further limited or even reversed by taking ex ante steps to increase educational attainment so that more workers benefit from foreign capital-skill complementarities, and by ex post measures that redistribute income to the disadvantaged.