Market News

The Mission to Electrify Africa Might Finally Be Under Way - BLOOMBERG

Plunging solar panel prices and international funding are now spurring the rollout of so-called mini grids that can transform rural communities

By Antony Sguazzin and Taonga Mitimingi

Photography by Zinyange Auntony for Bloomberg

When strips of solar panels arrived in his remote village in northeast Zambia, Damaseke Mwale saw an opportunity. He bought land, built a house and set up businesses including a grocery store and a hall to charge people to watch football matches.

“From there, that’s where my life changed,” Mwale, 41, said as he sat in his living room next door to his small store. Even his children’s school grades improved because they were able to study at night, he said.

Mwale is one of the early beneficiaries of a technology that promises to electrify a continent that’s home to more than 80% of the world’s 680 million people who live without power.

Called mini-grids, they generate electricity for small communities that aren’t on national supply networks — and the economics suggest their time may finally have come. Plunging solar panel prices, more business-friendly regulation by African governments and international funding are now spurring a rapid rollout from Nigeria to Madagascar.

In January, the World Bank launched a program to get power to 300 million Africans by 2030, a project that could attract $85 billion or more of investment.

“We’re in the inflection point,” said Yariv Cohen, co-founder and chief executive officer of Ignite Power. The Abu Dhabi-based company is acquiring the African mini-grid business of French utility Engie SA, which provides power to Mwale. “We’ve never had $30 billion allocated for energy access in Africa. We never even had $1 billion.”

It’s hard to know exactly how many units currently exist. Manoj Sinha, CEO of Husk Power Systems, the world’s biggest operator of solar mini-grids, reckons Africa could eventually see 200,000 of them. Cohen is more conservative, given there are only hundreds at the moment, he said.

Key to the success of the World Bank initiative, called Mission 300, is the buy in from governments when it comes to tariffs and fostering private investment, and there are cautionary tales that have deterred investors in the past.

There’s also the current political climate. President Donald Trump’s administration in the US, which is the World Bank’s biggest shareholder, is slashing development aid and has expressed disdain for renewable energy.

But the potential impact is clear, as is the incentive for richer countries to make sure the finance is there, according to World Bank President Ajay Banga.

Access to electricity in the sub-Saharan region ranges from 1% of the population of South Sudan to 94% in South Africa. Improving the average is key to development on the world’s poorest continent, which in turn is in the national interest of the Western world, Banga said.

“What this does is it develops jobs and industries and productive, consuming individuals in these countries,” Banga said in an interview in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. “If it reduces illegal migration, if it keeps people happy in their countries, if it creates marketplaces for your products and your intellectual property and your technology, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

About 30 heads of state and governments attended the January conference and a dozen nations presented detailed plans as to how to achieve universal access to electricity. The Democratic Republic of Congo, with $35 billion, and Nigeria, with $27 billion, presented the biggest proposals for investment.

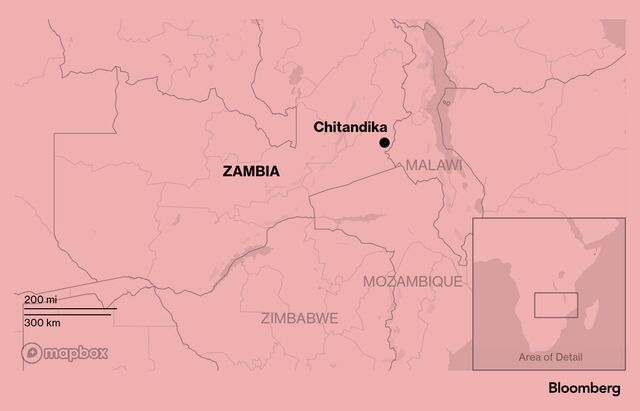

In Zambia, Mwale’s village of Chitandika in the Chipangali district got its mini-grid in 2019. The country has since embarked on a plan to bring power to 1,000 rural communities over the next few years, up from 45 now. The program is supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, the European Union, the UN and the Beyond the Grid Fund for Africa, whose donors include Australia, Germany and Sweden. It has an initial target of installing at least 200 more by the end of next year.

Zambia Plans to Bring Power to 1,000 Rural Communities

The village of Chitandika now has a solar-powered mini-grid

The Chipangali area has turned into a hive of activity thanks to the arrival of the solar panels, from a brightly lit barber shop to schools being able to provide more IT support for kids without having to use expensive petrol-fueled generators.

One headteacher, Tryson Banda, said the whole environment has changed, with better lighting and more appliances. His school has gone from having six teachers to 28 because it’s a more attractive place to work.

Simon Makowani, a local mechanic, is able to offer welding rather than having to take customers elsewhere in the province. It means if someone just wants to weld an oxcart, they can now do it in the village. “Before the grid, I was just doing mechanics,” he said. “I started welding and it has helped me a lot in terms of earning my revenue.”