Market News

Falling UK House Prices: Winner and Losers - BLOOMBERG

By John Stepek

Falling House Prices

If you’re keen to follow what’s going on at the COP27 summit, here’s some good news — Bloomberg.com is lifting its paywall for Bloomberg Green and providing all of its content for free through November 18. Follow the coverage here.

I’m not breaking any news here when I say that Britain’s housing market is in trouble and heading for more. Alongside surveys from Halifax and Nationwide pointing out that prices fell in October, we also have less-than-cheerful results from housebuilders starting to roll in.

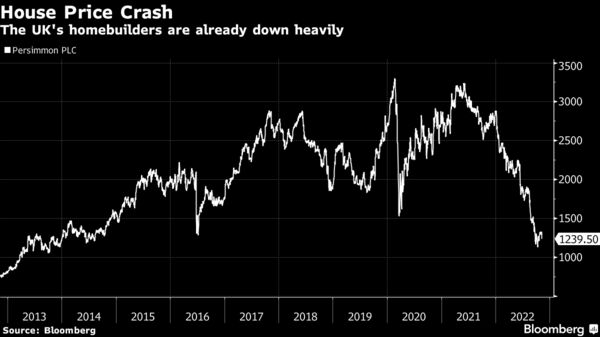

Persimmon, Britain’s biggest housebuilder by market value, saw its shares drop sharply this morning as it warned that it’s going to “implement a new capital allocation policy” — ie cut the dividend — as costs mount and sales fall.

Sales are down from 0.78 a week this time last year, to an average of 0.48 in the last six weeks. Cancellation rates have shot up to 28% in the past six weeks, from 21% in the 12 weeks prior to that. Rivals Barratt and Bellway were also downbeat when they updated last month.

Persimmon’s share price has more than halved in the year to date, so investors were presumably at least braced for grim tidings. And it makes sense that a wobbly housing market is bad news for those who owns shares in housebuilders, not to mention for any overleveraged landlords who can’t afford to ride this out.

But what with the way we talk about house prices “crashing” and the efforts that governments go to in order to keep prices on the upwards path, you’d think that a fall in house prices was an unmitigated disaster.

Far from it. In fact, when you look at it more dispassionately, falling house prices — in isolation — should create at least as many winners as they do losers.

The Winners

Take home-movers. Say you own a two-bedroom home worth £200,000. You have a growing family. You want a third bedroom. Three-bedroom homes in your area cost £250,000. So you need to find £50,000 to trade up.

Say house prices then rise by 20%. Your two-bed is now worth £240,000. Crack open the champagne! But wait — the three-bed you want is now £300,000. If you want to trade up, you now need to find £60,000.

Say that instead, house prices fall by 20%. Your home is now worth £160,000. Disaster! But wait — the home you want to move up to is now worth £200,000. So now you only need to find £40,000 to trade up.

This is all before you consider estate agent’s fees — percentage based — and stamp duty thresholds. So if you’re on your way “up” the property “ladder,” falling prices are not necessarily a problem.

Or how about first-time buyers? According to Nationwide, the average house price in the UK is now just under £270,000. Let’s knock that down to £250,000 for convenience and also because first-time buyers are probably paying less than that in many parts of the UK (or admittedly, a fair bit more down south).

Assuming you’re buying in England or Northern Ireland, you don’t need to pay stamp duty at £250,000, which keeps the sums even easier. (Wales and Scotland have different stamp duty rates).

So you’ve saved hard, or at least, the Bank of Mum and Dad has, so you have a 20% deposit — £50,000. You need to borrow £200,000. Problem is, although you earn more than the UK average, an annual salary of £40,000 only gets you to a loan of £180,000 (assuming the bank is only happy to lend 4.5 times your salary). So you have to wait.

A year later, prices have fallen by 20%. The house now costs £200,000. You still have your £50,000. You only need to borrow £150,000. The bank has pulled in its horns a bit because of the crash, but it’ll still go to four times salary, which is more than enough for you to get your loan.

So for first-time buyers and others who don’t currently own a property but would like to, falling prices are outright good news.

The Losers

Falling prices are good for those who want to trade up, and they’re good for those who don’t own a house. So who are they bad for?

The most vulnerable are those who have only recently bought their first home with a small deposit. Say you just bought your first home for £150,000 with a 5% deposit and a £142,500 mortgage. Prices fall by 20%. You now own a home worth £120,000 — less than the mortgage. That’s called “negative equity,” and it causes you two main headaches.

Firstly, if you have to remortgage, the range of deals open to you will be small if not non-existent, which means you’ll have to pay the most expensive rates going. Secondly, if you want to sell, the price you fetch may not be enough to pay off the mortgage, which means you’ll have to find the excess elsewhere. In other words, it makes moving almost impossible.

This is why it’s important, as my colleague Neil Callanan points out here, for first-time buyers to try to find a property they are happy to live in for a while. It doesn’t have to be the “forever home” (it almost certainly can’t be) but there is always the possibility that you might be stuck there for longer than you think.

Those who no longer want to trade up but instead want to use their home as a top-up to their pension pot, also lose out from falling prices. Whether you plan to use equity release, or to “downsize,” the amount of money available for consumption will have fallen. Given the huge growth in prices over that time, it’s hard to see this as a disaster, but it’s certainly a loss.

The Real Problem

In short, as with just about anything else, falling prices are good for those who want more of a thing (net buyers), bad for those who want less of a thing (net sellers), and catastrophic for those who have overstretched themselves on the borrowing front.

That takes us to the real problem with falling house prices — which is that they tend to coincide with harder economic times. House prices are falling now because interest rates are rising, which in turn is because inflation remains high.

But falling house prices can themselves can start to feed back negatively into the wider economy. Homeowners spend less because they feel less well-off, fewer house moves mean spending on furnishings and other goods falls, and banks start to be stingier about lending because they worry about bad debts building up.

The hope is that we can avoid the worst this time because the proportion of people exposed to falling house prices is lower than it was in the 2008 crash, for example, while many more mortgages are on fixed rates than they were last time.

But the main determinant of whether this goes from being a potentially benign slump to a full-blown crash, is employment. If people keep their jobs, they keep paying their mortgages. If they don’t, that’s when repossessions and forced selling starts to kick in.

If there are any lessons here, it’s perhaps that we should be less keen to cheer house price booms during the “good” times because the inevitable busts always make the bad times worse. Instead, we should focus on what we can do to achieve a more stable market over time. That’s a topic for another day.

But just before I go, here’s a top tip from my experiences as a home buyer and renter which I thought might be useful to you or anyone you know who’s starting on their journey down the property hellhole — sorry, I mean “up the property ladder”. Always, always, always speak to the neighbours before you buy (or rent) a property.

Firstly, they will a big impact on your quality of life, so take any red flags seriously. Secondly, they are a fantastic source of information about the things an estate agent won’t tell you and that you might otherwise miss. I can’t think of a single property-hunting tip that has saved me more heartache than this one.

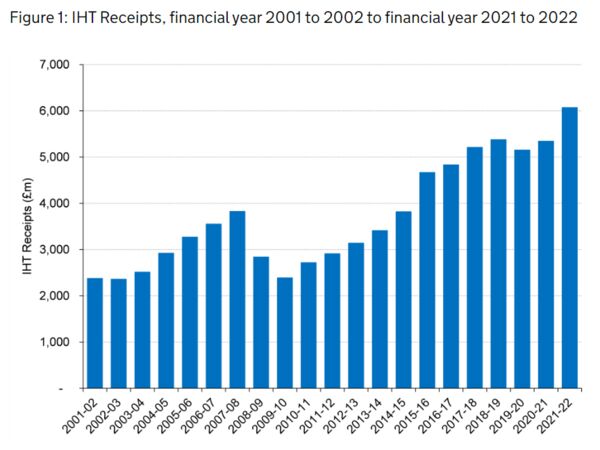

Today’s great pre-Budget/Autumn Statement/whatever they’re calling it now rumour is that chancellor Jeremy Hunt will freeze the inheritance tax threshold in a “stealth raid.”

The point at which your estate starts to become liable to inheritance tax (payable at 40%) is currently £325,000 for an individual, £650,000 for a couple, and up to £1m effectively for a couple who own a house worth at least £350,000.

The “nil-rate” threshold has been frozen at £325,000 since 2009. It’s already set to stay there until at least 2025/26, and now the rumour is that Hunt will leave it there until 2027/28.

This is a classic example of “fiscal drag,” whereby the government increases its tax take purely through the power of inflation. As such it can be viewed as a “stealth” tax although voters are increasingly aware of the wheeze. It has certainly worked very well for inheritance tax receipts over the last couple of decades, as the chart below from HMRC demonstrates.