Market News

Nigeria's people to pay for poor government policy - QUEENSLAND COUNTRY LIFE

Grain Brokers Australia

Nigeria's central bank took to Twitter last Friday to announce the extraordinary step of cutting off the supply of foreign currency to importers of wheat and sugar.

The embattled country is attempting to conserve US Dollar reserves amid a domestic recession and spiralling foreign debt.

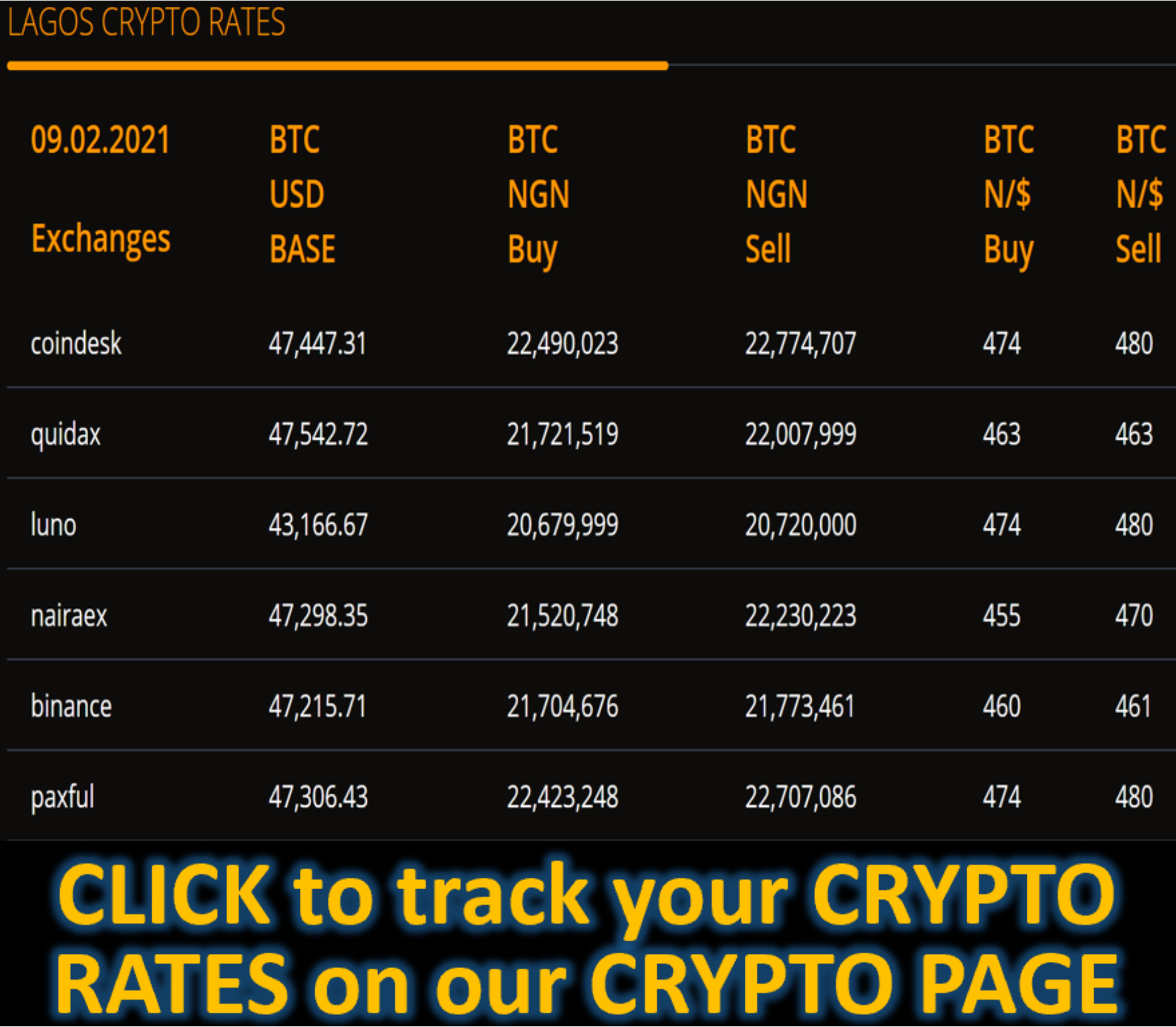

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) was a big seller of hard currency in foreign exchange markets on Friday, pushing the Nigerian naira to a record 437.62 against the US dollar.

And rising food costs continue to be the key driver of inflation, with the annual rate increasing 1.6 per cent last month to 22.95 per cent.

The oil-rich nation of Nigeria relies heavily on food and agricultural imports, which are valued at more than US$10 billion annually, to feed a population that recently soared above 210 million.

But low oil prices and ongoing COVID-19 lockdown restrictions have stifled Nigeria's economy and increased borrowings.

Revenue from oil and gas exports fund 90 per cent of the country's annual budget.

Nigeria is Africa's most populous nation and the continent's biggest economy.

In 2015, the CBN implemented a foreign exchange (FX) restriction list for 41 items it believed could be produced locally, instead of imported.

The currency controls were designed to ease pressure on the local currency amid a shortage of US Dollars.

But these led to skyrocketing inflation and further weakened the naira, making imports more expensive in local currency terms.

The CBN list has now expanded to 44 items, with corn added in July 2020.

In 2019, the government banned access to FX for dairy imports in a bid to stimulate domestic production.

This infuriated industry groups, which argued that domestic milk production was not enough to meet local demand.

After months of discussion and protests, the CBN was forced to lift the FX restrictions in February 2020 for six firms to import milk.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Nigeria's wheat production in the 2020-21 season will be a paltry 60,000 tonnes.

That equates to 1.2 per cent of domestic demand, which is forecast to be 4.95 million tonnes this marketing year.

That is despite 10 years of collaboration between the government, flour millers and farmers aimed at greatly reducing imports by increasing local wheat production to 50 per cent of domestic demand.

The Nigerian government collects a 5 per cent tariff on all wheat imports, and another 15 per cent levy that is earmarked for the national wheat development program.

Despite Nigerian millers' preference for imported wheat, the government is requiring millers to purchase local wheat at a fixed price of US$400/t - which is well above international values.

But the farmers prefer to sell their limited production to the Sahel countries to the north and non-government organisations (NGOs), which feed displaced citizens in the crisis-torn northern regions of the country - where terror group Boko Haram continues to commit atrocities.

According to the UN Refugee Agency, violence perpetrated by Boko Haram has affected 26 million people in the Lake Chad region and displaced 2.6 million since 2009.

The USDA has Nigeria penciled-in for wheat imports of 5.5 million tonnes and about 500,000 tonnes of exports - as wheat flour - to landlocked Sahel countries to the north, namely Niger, Chad and Mali.

The expected import volume is up 3 per cent from the previous year and 18 per cent higher than in the 2018-19 season.

Only 50,000 tonnes of wheat goes into domestic livestock rations, which means 99 per cent - or 4.9 million tonnes - of Nigerian wheat demand is for human consumption.

About 70 per cent of the flour milled from wheat goes into food products, such as bread, semolina, pasta and other wheat flour items.

Russia, the USA, Black Sea exporters, the European Union, Canada and Australia are the major wheat suppliers to Nigeria.

Relative prices and sea freight rates determine their market share from season to season.

Bigger exportable surpluses and lower prices out of the Black Sea region have increased the market share from that part of the world in recent years.

Nevertheless, imports of cheaper wheat from the Baltic states of Latvia and Lithuania have also grown - as domestic millers try to reduce the price of flour and increase their profitability.

The mills are blending the low-quality Baltic wheat with more expensive, higher quality, Hard Red Winter wheat from the USA.

Australian milling wheat is also popular with Nigerian manufacturers - when prices allow.

More than 300,000 tonnes was exported to the West African nation in 2017, and 60,000 tonnes was shipped in February this year.

The changing market dynamics have reduced the market share of US-origin wheat from a high of 91 per cent of Nigerian imports in the 2010-11 marketing year to just 35 per cent in 2019-20.

That said, Nigeria has consistently been either the second or third biggest buyer of US wheat since the 2015-16 season - importing between 836,000 tonnes and 1.09 million tonnes annually.

Last week's announcement by its government appears to be one more in a series of ill-thought-out policies aimed at reforming food production in Nigeria.

This season's wheat harvest is happening right now, and the next crop is not planted until November.

The harvested area is estimated to be about 60,000 hectares, which is relatively unchanged from levels of the past six years and puts the average yield at just 1t/ha.

The domestic market in Nigeria cannot possibly react to the government's new policy and feed the huge population without imports.

If its government's stated goal of 50 per cent self-sufficiency is to be achieved, it would require an additional 2.4 million hectares of land for wheat production - using existing agronomic practices.

This would mean a reallocation of corn and sorghum hectares and would jeopardise Nigeria's self-sufficiency status for those commodities.

The FX limit is a desperate move from a government rife with corruption and an abysmal economic management record.

The policy will affect almost the entire population, and its people will simply be collateral damage if the policy is implemented.

There will be a local reaction, but will it be enough to sway the policy makers?